Saturday, 30 October 2010

Thursday, 28 October 2010

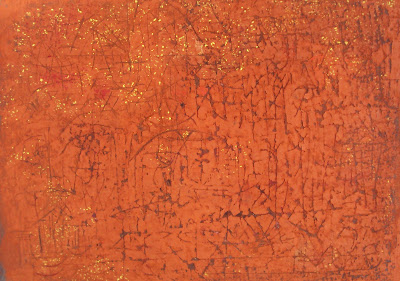

Art Perception

Static two-dimensional pictorial art - traditional drawing and painting - is the only art where the whole can be perceived in a single, simultaneous act of perception. With literature the mind scans along some point within the whole, as with music, film, theatre, ballet, etc. The act of perception with those forms is time-bound or related. They could be likened to streams progressing from A, the start, to B, the finish, and both the piece and one's mind are progressing together along the journey. Perhaps one can form some kind of inchoate sense of the total form after the event, a bird's eye view of the whole, but this is obviously not a direct act of perception. With these time forms all kinds of digressions are possible to the artist, harmful or not to the unity of the whole. but with the traditional pictorial forms, since the whole can be perceived simultaneously a greater rigidity is required, there is more absolute necessity for unity. Just to add that this simultaneity of perception of the whole is no longer there when the viewer focuses in on certain details and, because of the nature of perception, attention is now centred on aspects of the whole. In the creative process this focusing on details is where the artist may lose himself in 'digressions' - at the more obvious levels, say very intricately painting an eye but not standing back from his work to see that that eye is not positioned correctly.

That the static visual forms may be perceived directly as a whole is not meant as a value judgement - it is simply the way things are, though there is certainly an aesthetically satisfying aspect to this. Just to mention that the three-dimensional forms of sculpture do not quite exist in the same simultaneous way as objects of perception as naturally if one is looking at the front of a piece one cannot simultaneously be looking at the back of it.

That the static visual forms may be perceived directly as a whole is not meant as a value judgement - it is simply the way things are, though there is certainly an aesthetically satisfying aspect to this. Just to mention that the three-dimensional forms of sculpture do not quite exist in the same simultaneous way as objects of perception as naturally if one is looking at the front of a piece one cannot simultaneously be looking at the back of it.

Sunday, 24 October 2010

Language and Life

As written previously on the nature of language, the meaningfulness of this language if correctly used is inescapable, and to even attempt to question this involves the acceptance that the language used in the questioning is a meaningful act, and so to question language's meaningfulness is a self-contradictory, false and impossible act. This is in the same sense that to involve oneself in mathematics inescapably rests on the intrinsic truthfulness of the language of mathematics.

It would be wrong so imagine that this meaningfulness of language is at any point a subject of debate, a rational truth towards which one reasons, and once if successfully done, the point from which one can then meaningfully proceed with further reasoning. One doesn't need nor ever needed to prove mathematics to be true before engaging in it; instead its meaningfulness is an inescapable given, and it is the same with this language of words. The argument as to its meaningfulness has already proceeded as a matter of course from the imagined conclusion, that is, its meaningfulness.

It might be argued that language is true because it mirrors external life. To look at a case of a farmer with two fields in which are cows. In the first field are 35 cows, in the second 42. If all those from the second are brought into the first, one knows for certain if no cows have been added to or departed from their fields, that there are now 77 cows in that field - as a matter of language, one comes to this conclusion, since 35 added to 42 comes to 77. To stress also that this truth is not a servile but an autonomous one, by which I mean it is not some historical matter of observed truth that 35 and 42 are 77, and we then proceed into future time with this realised. Instead it is purely a matter of language. Language needs no observation of external reality to make such deductions; instead such truths are embedded within language. People might balk at this as mystical, but that would be because they are at odds with the intrinsic meaningfulness of life, have painted themselves into some false corner.

So the internal laws of language reveal this unquestionable truth, and if subsquent to this mental arithmetic the slightly sceptical farmer, to be asbsolutely sure, then counts all the cattle, the pleasing truth that external observation and logical deduction will be seen to correspond perfectly. Language and 'external truth' correspond as a matter of course. In this above instance though things are perhaps a little subtler than superficially appears, as the 'observed truths' of there being 35 and 42 cows are themselves matters of language before any arithmetic occurs. Obviously perception is the first mover of this process but to count to 35 is itself a linguistic matter. Perception is not able to stand alone in the matter of any observed truths. Language is always involved in matters that end in linguistic statements!

As a general and absolute principle, the perfect correspondence or co-existence of properly functioning language and life is not an idea regarding which one has an opinion. It is not up for debate, the same as it is intellectually impermissible to question 2+2=4. Any engagement in language, such as the attempted cannot but accept itself as a meaningful act within life. As I wrote here "The position of Doubt is a nihilistic intellectual proposition in the true sense, within the framework of which one cannot grant oneself the liberty of believing language to be real and intrinsically meaningful. And so, within this framework of doubt the question of doubt cannot be asked, as to ask the question requires an acceptance of the very reality or meaningfulness of language which Doubt, if true to itself, must doubt. And so, since the question of doubt cannot be formed, then doubt cannot exist, as doubt requires a mind utilising language so as to doubt."

The mathematical scenario with the cows is a very simple and clear example of this correspondence of language and truth, but this correspondence extends without limits, though of course with absolute dependence on the correctness of the language. Again to illustrate using mathematics, this world of numbers 'invented' in and by our minds, at no matter how seemingly abstract and complex the levels, always corresponds to internal truths of the external world. And why? Because life is not self-contradictory but intelligent, and seamlessly so. And this is where the relationship of life and language begins to deepen. This language of words is far subtler than the mathematical one, but if correctly used it will inescapably correspond to some truth of life. Though on the one hand language can be autonomous, self-sufficient as a truth-tool, it does not exist autonomously; that is, language dwells in life and without life naturally there would be no language.

However, a rampant mistake is to talk of life, or reality, and language as distinct. Reality is all that exists within itself, and in fact there is no within itself - what is 'within reality' is reality. And so language as dwelling within reality is inescapably part of reality, and thus the perfect correspondence of the two, if correctly used - for language is apparently capable of error and so creating illusory 'realities', things that seem to be but are not, even if believed by any numbers of people. Also, pedantic as it might superficially seem, 'reality' or 'life' are themselves words, and one cannot talk of these as though they were not words, nor pretend that the total realities to which such all-inclusive words like 'life' referred even somehow excluded those words as comprising inseparable aspects of those realities. There is no life existing independently of language, the same as there is no life independent of anything that forms part of the whole that is life, including for example the glass near my hand, or my hand or you yourself. To talk of life as though it did exist separately of the words being used to talk of it is meaningless language, where the integral relationship of words and that to which they refer has broken down, and one is merely left with linguistic unreal illusion.

So language and life are not distinct from each other, in fact there is no 'and' about it. Instead language - mathematical and linguisic - are extensions and deepenings of that life, and thus the lack of inner contradiction between them. Language does not dwell in some compartment apart!

It would be wrong so imagine that this meaningfulness of language is at any point a subject of debate, a rational truth towards which one reasons, and once if successfully done, the point from which one can then meaningfully proceed with further reasoning. One doesn't need nor ever needed to prove mathematics to be true before engaging in it; instead its meaningfulness is an inescapable given, and it is the same with this language of words. The argument as to its meaningfulness has already proceeded as a matter of course from the imagined conclusion, that is, its meaningfulness.

It might be argued that language is true because it mirrors external life. To look at a case of a farmer with two fields in which are cows. In the first field are 35 cows, in the second 42. If all those from the second are brought into the first, one knows for certain if no cows have been added to or departed from their fields, that there are now 77 cows in that field - as a matter of language, one comes to this conclusion, since 35 added to 42 comes to 77. To stress also that this truth is not a servile but an autonomous one, by which I mean it is not some historical matter of observed truth that 35 and 42 are 77, and we then proceed into future time with this realised. Instead it is purely a matter of language. Language needs no observation of external reality to make such deductions; instead such truths are embedded within language. People might balk at this as mystical, but that would be because they are at odds with the intrinsic meaningfulness of life, have painted themselves into some false corner.

So the internal laws of language reveal this unquestionable truth, and if subsquent to this mental arithmetic the slightly sceptical farmer, to be asbsolutely sure, then counts all the cattle, the pleasing truth that external observation and logical deduction will be seen to correspond perfectly. Language and 'external truth' correspond as a matter of course. In this above instance though things are perhaps a little subtler than superficially appears, as the 'observed truths' of there being 35 and 42 cows are themselves matters of language before any arithmetic occurs. Obviously perception is the first mover of this process but to count to 35 is itself a linguistic matter. Perception is not able to stand alone in the matter of any observed truths. Language is always involved in matters that end in linguistic statements!

As a general and absolute principle, the perfect correspondence or co-existence of properly functioning language and life is not an idea regarding which one has an opinion. It is not up for debate, the same as it is intellectually impermissible to question 2+2=4. Any engagement in language, such as the attempted cannot but accept itself as a meaningful act within life. As I wrote here "The position of Doubt is a nihilistic intellectual proposition in the true sense, within the framework of which one cannot grant oneself the liberty of believing language to be real and intrinsically meaningful. And so, within this framework of doubt the question of doubt cannot be asked, as to ask the question requires an acceptance of the very reality or meaningfulness of language which Doubt, if true to itself, must doubt. And so, since the question of doubt cannot be formed, then doubt cannot exist, as doubt requires a mind utilising language so as to doubt."

The mathematical scenario with the cows is a very simple and clear example of this correspondence of language and truth, but this correspondence extends without limits, though of course with absolute dependence on the correctness of the language. Again to illustrate using mathematics, this world of numbers 'invented' in and by our minds, at no matter how seemingly abstract and complex the levels, always corresponds to internal truths of the external world. And why? Because life is not self-contradictory but intelligent, and seamlessly so. And this is where the relationship of life and language begins to deepen. This language of words is far subtler than the mathematical one, but if correctly used it will inescapably correspond to some truth of life. Though on the one hand language can be autonomous, self-sufficient as a truth-tool, it does not exist autonomously; that is, language dwells in life and without life naturally there would be no language.

However, a rampant mistake is to talk of life, or reality, and language as distinct. Reality is all that exists within itself, and in fact there is no within itself - what is 'within reality' is reality. And so language as dwelling within reality is inescapably part of reality, and thus the perfect correspondence of the two, if correctly used - for language is apparently capable of error and so creating illusory 'realities', things that seem to be but are not, even if believed by any numbers of people. Also, pedantic as it might superficially seem, 'reality' or 'life' are themselves words, and one cannot talk of these as though they were not words, nor pretend that the total realities to which such all-inclusive words like 'life' referred even somehow excluded those words as comprising inseparable aspects of those realities. There is no life existing independently of language, the same as there is no life independent of anything that forms part of the whole that is life, including for example the glass near my hand, or my hand or you yourself. To talk of life as though it did exist separately of the words being used to talk of it is meaningless language, where the integral relationship of words and that to which they refer has broken down, and one is merely left with linguistic unreal illusion.

So language and life are not distinct from each other, in fact there is no 'and' about it. Instead language - mathematical and linguisic - are extensions and deepenings of that life, and thus the lack of inner contradiction between them. Language does not dwell in some compartment apart!

Thursday, 21 October 2010

Monday, 18 October 2010

Trapdoors

Trapdoors, the place was full of trapdoors; and the funny thing was that even after placing oneself unfortunately right above one of these trapdoors and the trapdoor swinging open and down one going, one didn't even notice it had opened nor down which the going. And as for the odd and unpleasant place one had gone and ended up . . . one didn't seem to notice that either.

Saturday, 16 October 2010

Friday, 15 October 2010

Art

"Tell us about your art."

"They're pictures that you look at."

"But what are they about?"

"Themselves."

"They're pictures that you look at."

"But what are they about?"

"Themselves."

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

Monday, 11 October 2010

Saturday, 9 October 2010

On the March

"They were on the march again."

"Again?! They'd never stopped."

"True, but now they were visible in their marching."

"Visible? They were always visible."

"Yes, but now they were more visible."

"And where were they off to this time?"

"The same place as always."

"Again?! They'd never stopped."

"True, but now they were visible in their marching."

"Visible? They were always visible."

"Yes, but now they were more visible."

"And where were they off to this time?"

"The same place as always."

Friday, 8 October 2010

Wednesday, 6 October 2010

Any Good

"Someone else's words - what good are they? No good."

"Well what about your own words? Are they any good?"

"No, they're no good either."

"Well what about your own words? Are they any good?"

"No, they're no good either."

Tuesday, 5 October 2010

Monday, 4 October 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)